Explore Christmas Nativity Traditions in Hawaii & Oceania

Explore unique Christmas Nativity traditions in Hawaii and Oceania, featuring beachside crèches, island-inspired celebrations, and festive décor made with local flora.

5/19/202510 min read

Introduction:

Did you know that in parts of the Pacific, Baby Jesus is laid in a canoe instead of a manger? 🌴 In Hawaii and Oceania, the Nativity story takes on a tropical twist with sun-soaked beaches, island customs, and vibrant traditions. Picture Mary and Joseph in leis and palm trees glowing with Christmas lights!

Whether you're planning a holiday trip or just curious about how others celebrate, this article explores the unique ways the Pacific honors the birth of Jesus. From Hawaiian songs to Fijian floral cribs, discover how Polynesian, Micronesian, and Melanesian cultures reimagine the Nativity with creativity and aloha. Let’s dive in!

Hawaiian Nativity Traditions

If you’ve ever experienced Christmas in Hawaiʻi, you know it’s not about snowflakes and pine trees—it’s about spirit, song, and a deep sense of place. The Nativity here isn't just reenacted; it's reimagined with aloha, layering the sacred story of Christ's birth with the living rhythm of island culture.

Mele: Sacred Storytelling Through Song

One of the most moving aspects of a Hawaiian Nativity is the integration of mele, or traditional Hawaiian songs. These aren't just background music—they’re reverent, poetic expressions of faith and community. I remember standing in a small outdoor chapel on Oʻahu, listening to a group of keiki (children) sing a mele about the birth of Jesus in lilting Hawaiian. It gave me chills. There’s a way the language bends around the story—soft yet powerful, like waves brushing the shore.

Tropical Beauty in Every Detail

Forget artificial snow and plastic poinsettias. Here, the crèche might be adorned with hibiscus, plumeria, or ti leaves—fragrant, vibrant offerings that feel alive. These plants aren’t chosen for aesthetics alone; each one carries cultural weight and symbolic meaning. It’s as if nature itself participates in the celebration. Isn’t that more fitting for the birth of the Savior?

Nativity on the Sand

Then there are the beachside Nativities—yes, literal beach scenes. Picture this: a sculpture of the Holy Family molded entirely out of sand, backdropped by the Pacific and framed by palms swaying in the breeze. No barn, no snow, but still deeply holy. You don’t need a stable to feel the sacredness. Maybe we’ve been too rigid with how we picture Bethlehem all these years?

Local Reinterpretations with Heart

What I love most are the bold, contextual reinterpretations: baby Jesus nestled in a canoe instead of a manger, Joseph wearing a pareo (a traditional wrap), and Mary with a lei around her neck. These aren’t gimmicks—they’re testaments to how faith roots itself in culture. It’s the same story, but told in a voice that speaks to the people here, in the climate they live in, with the materials they know.

Hula and Oral Tradition Bring It All to Life

And of course, hula. The Nativity in Hawaiʻi often includes hula as both prayer and performance. Watching a dancer use graceful, intentional movement to tell the story of the Annunciation or the shepherds—it’s emotional. Add in the storytelling tradition (moʻolelo), often shared aloud under stars or candlelight, and suddenly the Christmas story doesn’t feel 2,000 years old. It feels present. It feels lived.

This isn’t just pageantry—it’s theology in motion, uniquely Hawaiian but deeply universal.

Beach Nativities Across Oceania

What does the Nativity look like when the nearest stable is a canoe shed and the closest shepherd might be a fisherman? In Oceania’s coastal communities, the birth of Christ is retold not with European winter imagery, but with the textures, colors, and symbols of the sea. And frankly, it feels more real that way—more grounded in the daily lives of the people celebrating it.

Sand and Salt Instead of Snow

Across islands like Samoa, Kiribati, and the Solomon Islands, Nativity scenes are not confined to churches or living rooms. They show up on beaches—yes, right there on the sand, framed by ocean spray and coconut palms. The manger? It might be crafted from driftwood or woven pandanus leaves. And instead of hay, you’ll find palm fronds or hand-woven mats. There's something deeply moving about sacred moments unfolding in such open, elemental spaces. Why box up the divine?

Faith in Local Language: Case Studies That Speak Volumes

In Kiribati, church youth groups often sculpt entire Nativity scenes out of beach sand, decorating them with shells, coral, and island flowers. The community gathers at dusk, singing hymns as the sun dips into the Pacific. It’s not performance—it’s devotion.

In Samoa, local churches might stage live Nativities under fale structures (traditional open-air pavilions), where villagers participate in re-enactments that blend Biblical narrative with Samoan chants and dance.

In the Solomon Islands, some congregations set floating cribs in the shallows—literally placing the Christ child in a canoe or shell-covered basket on water, a poetic nod to both birth and baptism.

It’s striking how each island reclaims the story in its own idiom, its own materials, without ever losing sight of the message.

The Sea as Sanctuary

One detail that sticks with me is how marine life becomes part of the scene—not as decoration, but as symbolism. You’ll find fish motifs carved into manger structures, shells laid in patterns around the Holy Family, and boats carrying gifts instead of wise men. It’s not just quaint; it’s theological. After all, in a place where the ocean sustains life, how could it not be central to the celebration of new life?

The Beach Alters the Liturgy, Too

Christmas Eve services here aren’t held in candlelit cathedrals. They're outdoors—on the beach, under stars, the air thick with salt and song. People gather barefoot. You hear waves instead of pipe organs. There’s less pageantry and more presence. The setting strips things down, forcing the focus back to what matters: the child, the promise, the joy.

Some might call this unorthodox. I’d call it profoundly incarnational. Isn't that the whole point of Christmas?

Indigenous and Cultural Infusions

Christianity may have arrived in the Pacific through missionaries, but it didn’t flatten the region’s rich cultural identity—it adapted, blended, and was made local. Nowhere is that more beautifully evident than in the way Pacific Island communities infuse the Nativity story with indigenous traditions. It's not about mixing and matching—it’s about honoring both faith and heritage, side by side.

When Belief Meets Ancestral Beauty

It’s one thing to read about inculturation in a theology textbook. It’s another to see it—Jesus swaddled not in linen but laid gently atop finely patterned tapa cloth, a material made from mulberry bark and steeped in ancestral significance. In many communities, including Tonga and Fiji, tapa and woven mats are used not as backdrops but as sacred wrappings and altar pieces—physical reminders that this story, though ancient, is theirs too.

During one reenactment I witnessed in Vanuatu, the Holy Family wore traditional island attire. Mary wore a lava-lava, Joseph had a woven belt, and the angels carried palm fans instead of trumpets. Was it unconventional? Yes. Was it reverent and moving? Absolutely.

Sacred Movement: The Gospel in Dance

If you’ve never seen a siva (Samoan dance), haka (Māori ceremonial dance), or meke (Fijian storytelling dance) performed during a Christmas program, you’re missing something extraordinary. These aren’t add-ons—they’re part of the message. In many churches, dance is the sermon. It’s how the people express awe, lament, joy, and divine celebration. You can feel the intensity—sometimes even the trembling—in the room when these dances begin.

And yes, these performances can be fierce. Think of the haka: powerful, rhythmic, unapologetically physical. But isn’t that what the incarnation is too? God entering real, embodied life?

The Power of Language to Make Christ Known

One of the most beautiful elements of the Pacific Nativity experience is linguistic diversity. You might hear Luke’s Gospel read in Samoan, a hymn sung in Tok Pisin (Papua New Guinea Pidgin), and prayers offered in Māori. Each language carries its own cadence, its own spiritual texture. Hearing “Glory to God in the highest” spoken in Fijian or Tongan hits differently—it grounds the words, brings them home.

When we limit the Christmas story to English or Latin, we miss the deeper truth: Jesus was born into a specific culture, a real place. Why should His story not be told in ours?

Community Celebrations and Performances

In many Pacific communities, the Nativity isn’t just a quiet reading on Christmas Eve—it’s a months-long, village-wide celebration that pulls everyone in. And I mean everyone. From elders weaving decorations to toddlers dressed as sheep, the entire community becomes a living part of the story. You don’t just watch the Nativity here. You live it.

Church and School Pageants: Where Stories Are Planted Young

Growing up in the West, I always thought of Nativity plays as something confined to Sunday school stages. But in places like Samoa, Tonga, and the Marshall Islands, these pageants are so much more than simple recitations. They’re a centerpiece of the season—an expression of both faith and cultural pride.

Local churches and schools spend weeks preparing: hand-sewing costumes, learning dances, practicing verses in native tongues. It’s not unusual for multiple generations to be involved—grandparents coaching lines, teenagers choreographing hula or siva routines, younger kids learning their cues. It’s messy, noisy, joyful, and somehow always comes together.

Outdoor Festivals: The Nativity Spills into the Streets

Once the pageants end, the celebration doesn’t. Town squares and churchyards transform into open-air festivals with handmade crafts, locally prepared food, and music that makes you want to dance barefoot. Imagine eating coconut candy while someone strums a ukulele and kids run around in angel wings. It's festive, but it's not commercialized—it’s intimate. Grounded. Authentic.

What struck me most when I visited a Christmas market in Fiji was the presence of elders leading carols while vendors sold woven ornaments and hand-painted Nativity stones. There was no separation between sacred and everyday life—it all blended together.

Everyone Has a Part, and Every Part Matters

This is not a spectator sport. Elders pass down oral traditions. Aunties sew costumes and decorate the church with tropical flowers. Uncles help build stage sets or construct life-sized mangers out of bamboo. And the kids—keiki—they bring wide-eyed wonder to every line they stumble through.

There’s a humility in how everyone contributes. No role is too small. No one is too old. It’s a reminder that the story of Christ’s birth was, and still is, a communal story—one that depends on ordinary people showing up with what they have.

Village-Scale Nativity Displays: Built by Hands That Know Each Other

Some villages go all out. I’m talking full-scale Nativity scenes with structures you’d expect to see at a theater or a film set—only they’re built by neighbors, not professionals. People contribute coconuts, leaves, woven mats, fishing nets, and whatever else they can. It's not about perfection. It’s about participation.

There’s something powerful about a community creating something beautiful together—not for tourists, not for likes on social media, but for the shared joy of telling the greatest story ever told.

Eco-Friendly and Handmade Island Crèches

There’s something deeply spiritual about simplicity—especially when it’s made by hand. In the Pacific Islands, crèches (Nativity scenes) aren’t just decorative; they’re heirlooms, acts of devotion, and often, quiet statements about sustainability and sacred connection to land and sea.

Made from the Earth, for the Divine

Walk through a Christmas celebration in places like Tonga, Palau, or the Cook Islands, and you’ll see Nativity sets crafted not from plastic or glitter, but from the very elements surrounding the people who make them. Palm fronds folded into stars. Driftwood shaped into mangers. Coconut husks transformed into the robes of the Magi. These materials are not only sustainable—they’re meaningful. They speak of resourcefulness, reverence, and a relationship with nature that runs deeper than convenience.

And let’s be honest—there’s something far more compelling about a baby Jesus laid in a canoe carved from reclaimed wood than one molded from resin in a factory thousands of miles away.

Heirlooms Woven with Memory

In many families, Nativity sets aren’t bought—they’re inherited. A grandmother’s hand-carved angel. A woven donkey made by an uncle long gone. These pieces get brought out year after year, softened by time and rich with memory. I’ve seen crèches where every figure was handmade by a different family member. No two figures matched in scale or style, but together? They were perfect.

It’s not about polish. It’s about presence. About love shaped into wood and cloth.

Artisans Who Tell the Gospel with Their Hands

You’ll find artisans across the Pacific who’ve turned crèche-making into an art form. From Niuean carvers to Fijian weavers, these craftspeople don’t just create souvenirs—they tell stories. Jesus might be carved with features that resemble local people. The animals might be native to the region: pigs, sea turtles, even fruit bats. It's a theology of incarnation made literal: Christ born here, among us.

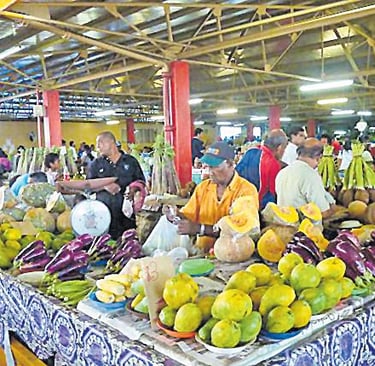

Many of these sets can be found in local markets during the Advent season. Markets like Suva’s Municipal Market in Fiji or the Talamahu Market in Tonga showcase intricate crèches alongside handmade candles, textiles, and food. But you won’t find many duplicates—each set reflects its maker’s hand and vision. If you ever pick one up, you’re not just buying a decoration. You’re taking home someone’s prayer in three dimensions.

Why It Matters

In a world drowning in mass-produced seasonal clutter, these island crèches offer an alternative: rootedness, intentionality, care. They remind us that the heart of Christmas isn’t shiny or mass-marketed. It’s humble. Handmade. Local.

And maybe that’s exactly how it should be.

Conclusion:

From candlelit beach masses to crèches made of shells and palm leaves, Christmas in Hawaii and Oceania brings the Nativity story to life with island warmth and cultural pride. 🌊 These tropical traditions not only preserve the meaning of the season but also celebrate the richness of local identity and faith. Whether you’re visiting or simply inspired from afar, take a cue from the Pacific—there are endless ways to honor the Holy Family, even in flip-flops.

If you’ve experienced a unique Nativity tradition—or made your own island-inspired crèche—I’d love to hear about it in the comments! Share the aloha and keep the spirit of Christmas vibrant and diverse.